‘Can I ask you a question? I was wondering about your ancestors; do you have any ancestors from the Mediterranean or The Middle East?’

‘Well . . .’

‘Ah, perhaps you’d like to be there now, in the Mediterranean?’ He was conspiratorial, trying to put me at ease, we both knew about the British weather.

‘I used to live there, the Mediterranean’, I said, not wanting to sound too eager to please.

‘North or South?’

‘Oh, I see.’

The Haemotologist was tall, slim, slightly stooped, as if from deference, rather than age, although he seemed near to sixty, with receding, crinkly hair and a trimmed, greying beard. Handsome face and eyes that looked like he enjoyed being intelligent and dapper and charming. Complexion of coffee colour; you’d say North African, with the clipped accent of the well-educated. He ran through the analysis of my blood at speed, noting where it was less than optimum. Quickly moving on to the next graph or table, always finding ways to reassure. My blood, with it’s laggardly white blood cells, who nonetheless, according to him, managed to get the job done, was universal amongst Africans, he said, wherever they are.

I could hardly keep up with the statistics he generously showed me on the computer screen as they scrolled by. Was it me, or did other patients understand these kind of things, well-versed by the medical pages of the Daily Mirror or Google? I dismissed the thought that all this — he shared his gorgeously hand-written notes, too — was for the benefit of the young female medical student who sat demurely behind my left shoulder. Kidney, liver, bone marrow and creatures known as the scavengers were his only concessions to my vernacular ignorance. How did he learn all this?

But mostly I was thinking about the journey. Exiled from the Dardanelles, when we got away from the Greeks, us no better than Helots. From Italy to Libya, when the Mediterranean was one, undivided. There we must have stopped off for a while, took on provisions, tarried, we might have called it; the Balearics, leaving behind our cairns; then Morocco, last pleasures and civilisation before the grim Atlantic, with its mist and black rocks and fierce gales, then to the edge of the world, Totnes, our New Troy, so called. Brutus would have left me there; he had bigger fish to fry. And my ancestors? After that we moved only when we had to.

‘So you’re saying that if I were African, my blood would be normal?’

‘Yes, that’s right.’ He was gently ushering me out of his office.

‘Thank you’, was all I could think to add.

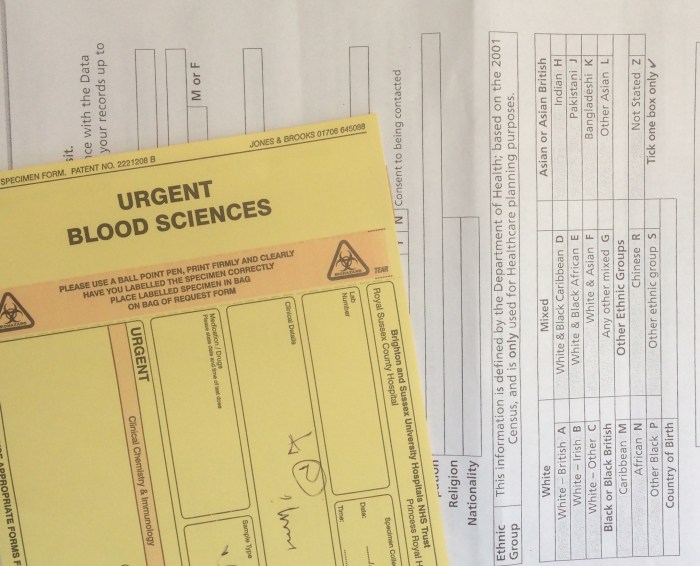

‘Don’t worry,’ he said, as I shook his hand. And I went off for another blood test.