A whodunit

“Well, it wasn’t me,” Steyne sounded offended, his voice smooth and clear.

“Never is” said Wilson in the kind of cockney drawl he used when he was sexually interested – not in this case – or felt his interlocutor to be beneath him.

“Now, now,” calmed Ghita. She left the “children” unsaid. They’d known each other for years.

Rachel looked startled, although she’d seen scenes like this many times before. Then Hurst threw in: “Maybe it wasn’t anyone?” He seemed to be making a philosophical point.

“So what happened, then?” Wilson was taking control.

“I came in, and the door to the office was open,” Ghita looked at Wilson for approval. “It shouldn’t be.”

“No, actually, you think it shouldn’t be.” Steyne went on the attack, his eyes fixed on Ghita. At sixty he could have been played by the same actor as at thirty, his years carried so little weight.

“We’ve been through that so many times.” Ghita tried not to sound flustered.

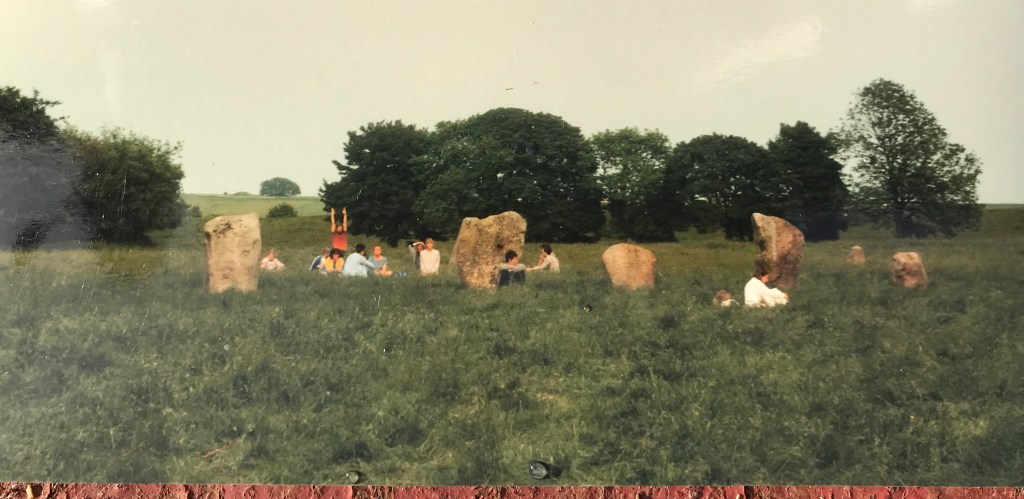

Hurst looked round, from face to face, then at the dull blue carpet. He wondered whose job it was to clean it. Sitting on cushions made it feel like a prayer meeting; he didn’t know if that was good or not. The room was in its perpetual twilight.

“Yeah, yeah,” said Wilson, not much more than grunting. He meant carry on.

“At first I thought . . . ” She looked at Steyne; they all knew what she was thinking. “And, so, I didn’t think anything was wrong. Anyway, I checked the answer machine.”

“Yes, yes.” Steyne said sharply; he wanted to get to the point.

“Was there anything on it, the voicemail?” Wilson was having fun, his heavy face lightening. Steyne laughed: they were friends again. Hurst noted the use of ‘voicemail’, Wilson had an ear for jargon, he thought. Rachel looked blank.

Ghita had to indulge them, she knew. “Then, I went to the top drawer to get some cash and it was open.”

“What was?” Wilson again.

“The drawer, it wasn’t locked. And the cash box. It was gone.” Ghita’s black hair had become even more unruly, as though joining in her disapproval.

“Well, I wouldn’t take it, would I?” Steyne sounded as though he had no need of money, he lived on a higher plane.

“Someone would.” Wilson added; he could have been rubbing his hands together. “What time was that?”

“About one, just before” Ghita, being practical.

“A bit late, then,” Wilson said. It seemed to be a private joke between him and Ghita, and she smiled.

“I know,” said Rachel. They all turned; they’d forgotten about her. “Why don’t we ask Woody? He’ll know what to do.”

“Woody?” said Wilson, disguising his hurt. “What could he do? He wasn’t even here.”

Woody Mathews held an honorary post; unluckily for Wilson he took it seriously. Rachel’s face had the glow of faith: “No, but he’ll know what to do.”

Ghita looked slighted on Wilson’s behalf. “That’s it, then” said Steyne, getting up, drawing the meeting to a close.

“I’ll give him a ring” said Hurst, as they knew he would.

*****

The room was in a semi-basement, light penetrated weakly through frosted windows with bars on the outside. It was odd-shaped, following the contour of the Victorian villa, an oblong with a cut off corner where a potted palm stood. There was no furniture, save some folded chairs stacked against built-in cupboards and the pastel coloured cushions on which they were sitting. On the cream painted walls were two high-quality reproduction mandalas while the walls themselves gave out a foggy, damp smell that mingled with stale incense. The carpet was enlivened with a wine-red kilim, its elaborate arrows pointing uselessly away from Mecca. Even when sitting on the floor the ceiling felt too low. The whole was like like a sanctified cave set among the flux and flow of desirable, capricious inner London.

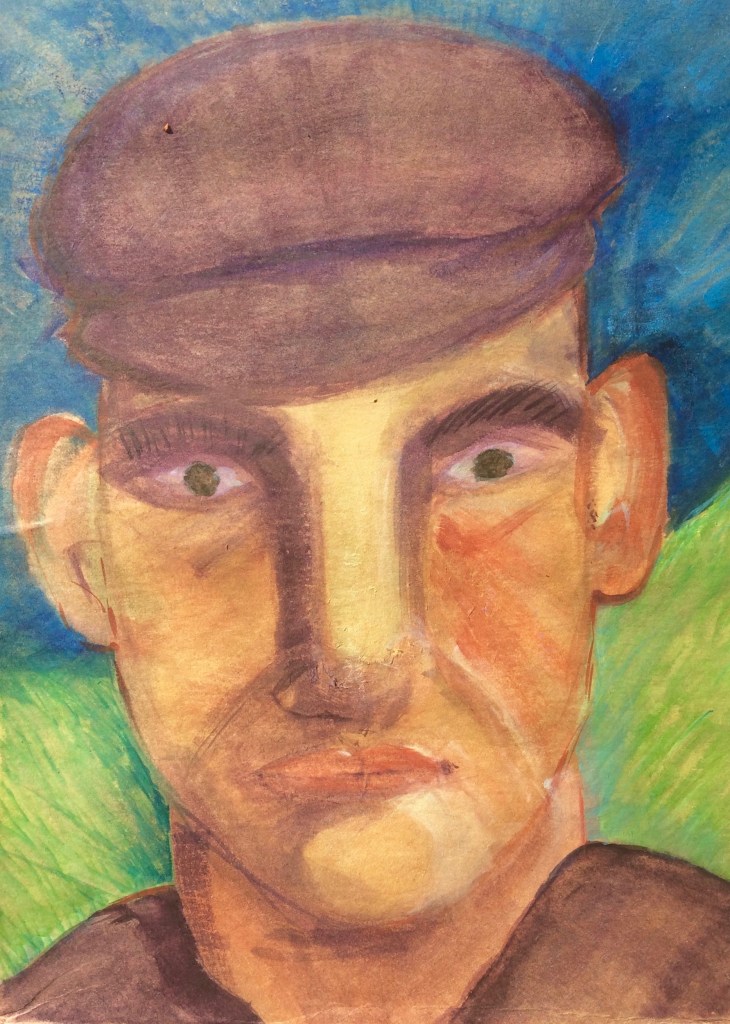

Woody’s face was uncorrupted and incorruptible; the ageing choirboy who believed the words he sang. He looked around; beside him the others seemed careworn, all except Steyne, steely as ever. None of them had had a good weekend.

“What about Simon? Wasn’t he about?” asked Woody, when they had all settled. He’d been waiting for a while.

“The yogi? No, he wasn’t. It couldn’t have been him.” Rachel was sure; even if he’d wanted to, he couldn’t, her face said.

“How much was in it?” Woody played the doctor, getting down to practicalities.

“Well,” said Ghita “there was the mindfulness course on Thursday, most people paid cash, they don’t have cheques, they think we can’t do cards . . .”

“We can’t, can we?” Woody wasn’t sure about the ‘we’.

“We can, actually, yes.”

“The wi-fi’s very bad. It’s very slow, we should get a new router,” Wilson put in firmly.

“Yes . . .” Ghita continued, “so most people paid cash. And there was the addicts’ group on Tuesday, they put something in.”

“Yes. But how much? How much was in it?” Woody was trying to be patient.

“I borrowed some, on Thursday about £20” said Hurst. He meant ‘took’.

“About?” growled Wilson. He was keen on semantics.

“Well, yeah, twenty, £20.” Hurst slurred slightly, but no-one paid him any attention, they moved on with only a murmur. He tried to forget about the drawer, which he’d left unlocked.

Ghita was leafing through a ring binder, at pale grey sheets of paper, photocopied and overwritten in different coloured handwriting. She was the only one who had brought along anything business-like; thoughtfully she’d also put out a large jar with a selection of biros, markers and pencils. The others glanced at it from time to time, but didn’t take from it.

“I don’t know how much from the addicts’” she looked briefly at Hurst, “but there were nine people on the course, three paid the full amount, and there were four concessions . . . it looks like two didn’t pay. There’s nothing here.”

“They arrived late. They paid me” snapped Steyne, reddened, continuing: “the usual amount.”

“He means concessionary,” said Wilson and Steyne looked at him gratefully.

“So, how much was that, altogether?” Woody pressed on.

Ghita had a ledger of some kind, it was scribbled with figures, notes and initials. It looked out of place, like money-changers in a temple. “And we sold a book,” she added, looking at Woody.

“But doesn’t that go into the bookshop safe, upstairs?”

“No, because it was from the library.”

“The library?” Now Woody was shocked.

“We don’t really need a library,” Wilson was sharing his superior knowledge “It’s all online. We should just sign-up to one of the universities.”

“It was Steve,” Ghita was determined to go on.

“Steve?”

“Steve Wednesday. The musician”

“What does he want books for?” Woody knew he sounded ridiculous, but he couldn’t stop himself.

“He’s into films, too,” Rachel piped to everyone’s surprise.

“It’s his wife” Wilson said with authority. “She’s very middle class. Catholic. A therapist.” He spoke as though he could handle them all.

“She did a session here. Last year” Added Ghita, to her own annoyance.

“Yes. It was packed” Rachel looked up, her face clouding with the memory of the lovely scents of the smart women, their intelligent voices and their shoes lined up neatly outside the therapy room, assured in their wealth.

“He wanted to buy the Waugh on Campion, the signed copy.” Explained Ghita, then added quickly, for the benefit of Rachel and Hurst: “Evelyn Waugh”. Woody stared at her.

“Christ!” hissed Steyne.

“At least it didn’t get nicked” said Wilson; Steyne suppressed a smirk. They were enjoying themselves. No-one added they needed the money.

Ghita tried to force some kind of order: “He said, well he gave us £240, that was cash too. He said he’d get us a replacement, too, you know, a modern paperback”

“Hardback” put in Wilson. “From Amazon.”

“Amazon?” Echoed Woody, perhaps surprised by their initiative.

“There was card from them, this morning.” For Rachel it was like a message from another world.

“Yeah, they tried to deliver them today. But there was no-one in. It’s at the post office. I’ll . . . “ Hurst’s voice trailed away.

“And a friend of yours came by” said Steyne, looking at Ghita, “on Friday.”

“The day . . . ?” she sounded alarmed. “What friend?”

“So you were here, in the morning?” Wilson spoke slowly.

“Yes, yes.” He wanted to get it over with, quickly. “I was here. Then I went out, to the gym. I thought you’d be here, too” he looked at Ghita and was suddenly very young again as she stared back, stoney. “Early, that is . . . a chap came to the door” he sighed, “he asked for you. The Asian lady who brings the flowers, he said, he seemed a bit upset, and you know, I thought you would’t be long.”

Ghita tried to take it in; she didn’t just ‘bring the flowers’ and she wasn’t really ‘Asian’, she considered herself ‘Anglo-Indian, actually.’ She composed herself: “So you just let him in?”

“Yes, yes . . .”

In the silence, they each began to fill in the story: the doorbell rings, Steyne, answers and a man – he’s in his early 20s, younger than most of the regulars, wearing a dark padded parka, zipped up – he says he’s come to see the Asian lady. Everyone knows her, she’s lived around here for years, shops in the market, puts out publicity. Steyne lets him in, it would’t be good form to ask for a name; he doesn’t show him into the reception, with the locked cabinet of books, the Buddha statue (a family heirloom, brought in by Ghita) and Rachel’s soothing semi-figurative paintings. Instead, with patrician friendliness, he leads him into the office, in the sub-basement.

The young man calmly takes his place in the comfortable battered office chair behind the desk, ignoring the two plastic ones. Steyne goes to make them tea in the small kitchen next door. He whistles to himself, uses the nice tea, the Darjeeling he keeps hidden. He has his own pot. But the milk, does he call out “Only soya, I’m afraid,” or root around to find Hurst’s little carton of full-cream? The man grunts back, indifferently.

After a while, Steyne returns and tries to make small talk: “She’ll be in soon” or “Have you done many events here?” but the man is abstracted, he doesn’t drink the tea. He gets up carefully, saying he’ll come back later; he pulls a small day bag over his shoulder. Steyne emits a few relieved pleasantries and the man sees himself out.

*****

They sat there, on their cushions. Hurst stared stupidly at the carpet, as though for comfort. He realised Steyne was gazing too at the same spot, his eyes lost. Hurst opened his mouth, words, a question, began to form: was – he – black? The others were all silent, as though at that moment receiving a benediction. He closed his mouth again.

“So. That was it, really,” said Steyne, shifting on his cushion.

“Why would anyone steal from us?” Rachel hoped for an answer, but she knew it would never come.

“Yes. I see,” said Woody with weary finality.

“I think we should all meditate,” offered Rachel.

“I’ve got to go and do some work,” said Wilson, briskly. Then added, as they looked at him with amazement “On my book.”

They muttered assent, as if to some higher mystery.

“I’ve got to go, too. I’m giving a talk tomorrow,” said Woody.

The rest looked on in wonder as the two men rose and sauntered side-by-side to the door. There was a brief business as Wilson ceded and let Woody leave first, then he passed through and shut the door firmly from the other side.

They gathered themselves into a circle, Steyne snorting audibly to re-assert seniority, then they sat there, like children determined to prove they could behave when the adults had left.