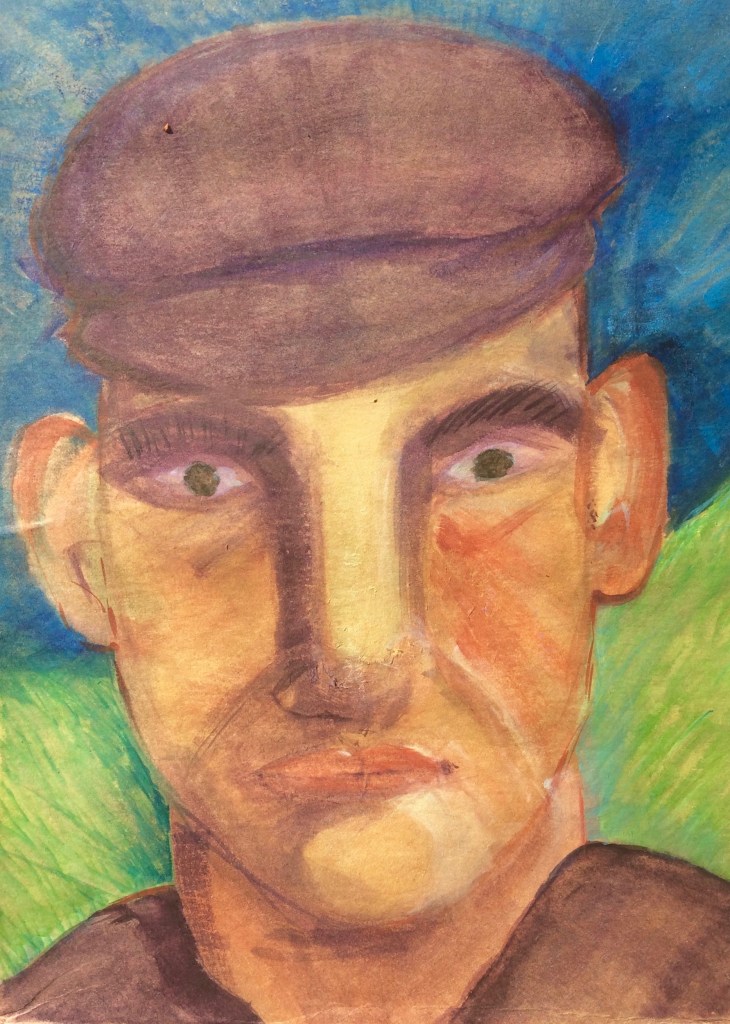

It was my dad who first took me to the cricket. A festival game in Weston-super-Mare, 1964. Dad holiday smart in his double-breasted blazer and open-neck shirt. Somerset those days were the team of Langford, Alley and Fred Rumsey. I left Somerset long before they ever won anything, long before the era of Richards and Botham (“Jus’ an o’d yokel” Dad called him). And after that time I don’t think we went together again or talked much about it, or played, other than on the beach (or quarry). Like other things, birding, say, he took me to the threshold and left me there.

The last Sunday in June, 2019 and a call from my brother told me Dad had had a fall. With my wife and daughter I took the train across the south of England. Shoreham by Sea, Lancing, Worthing, Angmering, Chichester: an incantation along the crowded south coast; inland, Salisbury, where, at other times, I’d jump off to see the cathedral, Warminster and its uncanny hill, Bradford on Avon and thoughts of its Saxon church, and onward. At Weston General Hospital he seemed as he had 18 months before following another fall: bones protruding, dun skin bruised and blotched, stony, but still vital. He died later that night.

Then the cricket came back. Here in Hove a few days watching Sussex at the County Ground; Test highlights on iPlayer in the evening and Day Passes to Sky TV: work was patchy and I needed to shut out the sun.

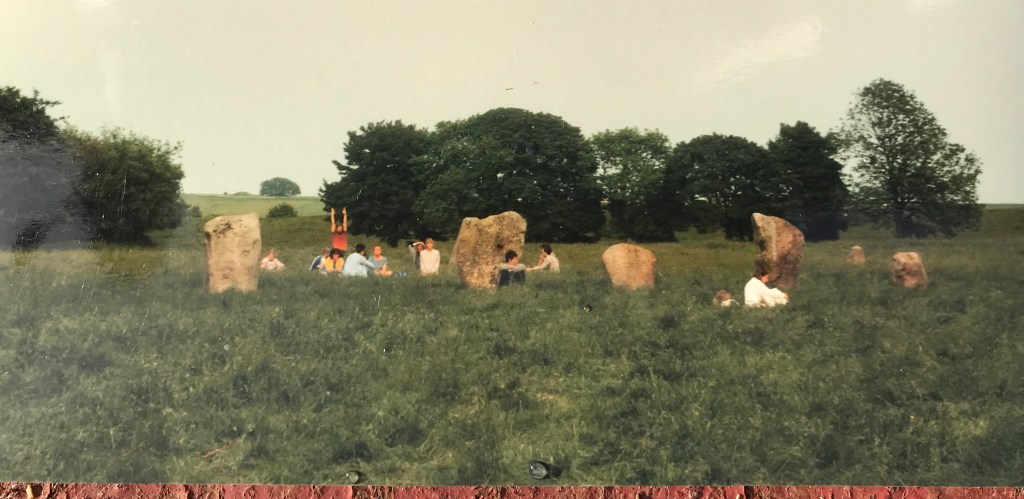

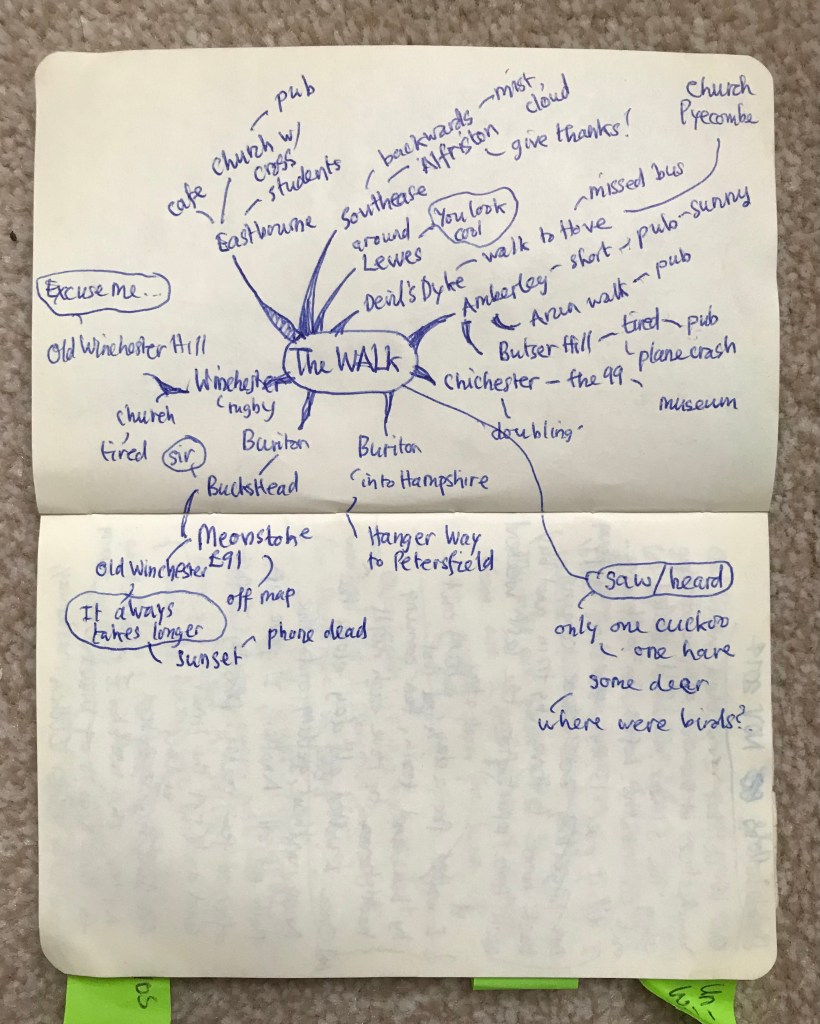

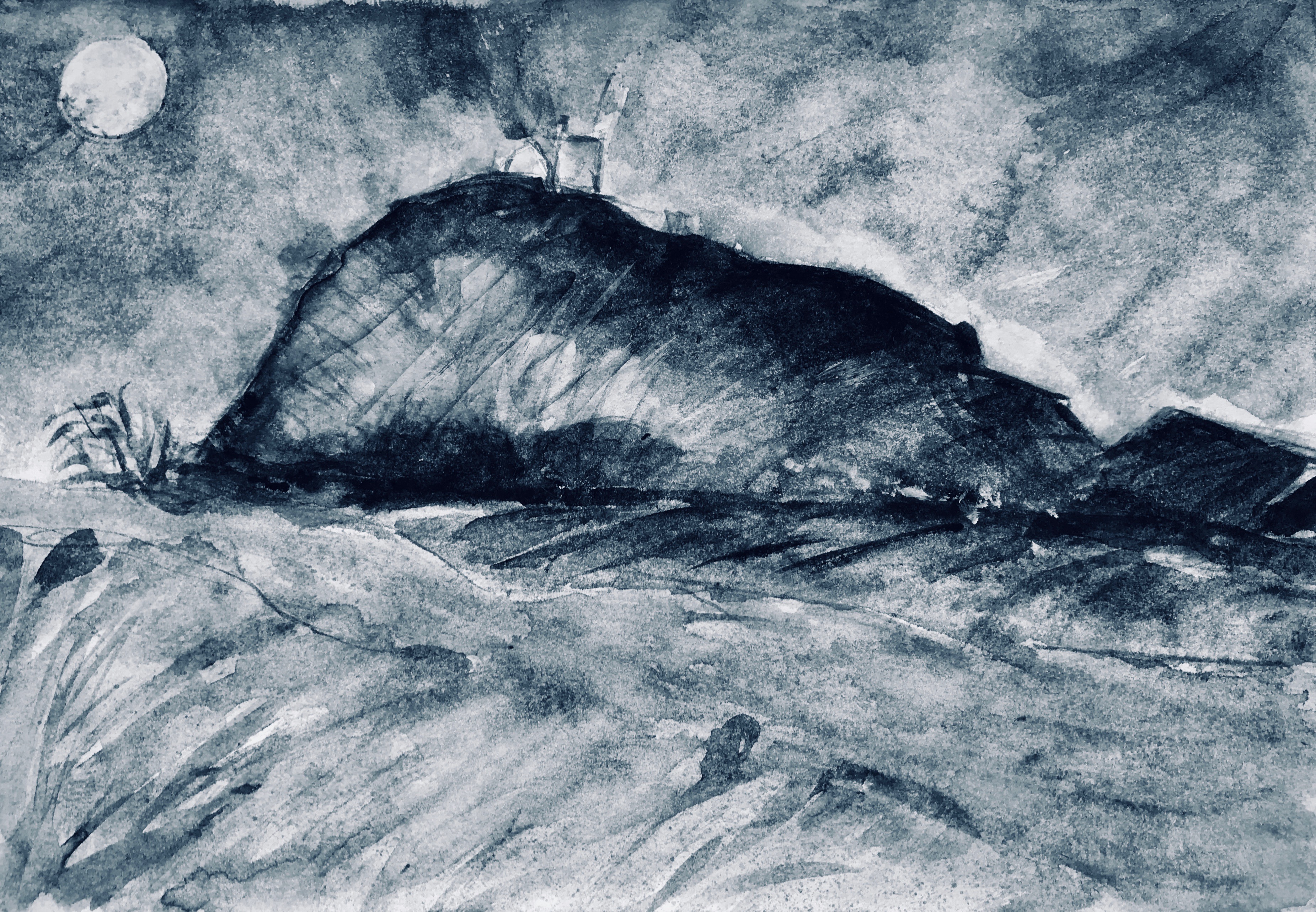

Sunday 25th August. I took the train to Lewes, then walked out of the town, onto the Downs at Southerham, up to Mount Caburn, then down into Glynde. Walking: something else my dad had left me. I knew there was a game on that day: the local club, Glynde & Beddingham were playing an MCC XI. The tenth anniversary of their winning the National Village Cup; I’d read a long article about it while working in Istanbul, fearing I was reading about the death of an England I hardly knew.

Outsider. Incomer. I did what I’ve always done: tried to fit in without standing out. Drank the local beer, sat just off from the clubhouse, chatted when I could with the members. I won a bottle of fizzy Chardonnay, the one that comes in a seductive bottle. Not quite won. I was first in line for the raffle but the Aussie in charge hadn’t worked out how to do it, so I went back to my seat empty handed. When I came back again all the tickets had been sold. Apologetically the Aussie handed me the only thing left, the wine.

By now his English mates were huddled over their iPhones in the lee of the clubhouse. Joffra Archer had joined Ben Stokes. He couldn’t could he, steal it for us in Sussex? That reverie didn’t last. Then came Jack Leach of Somerset, the last man. I stopped chipping in with the banter. I could see my dad’s dark lonely bungalow, smell its must and aged damp in the Weston-super-Mare he’d never left. “C’mon, c’mon” he was saying to the radio, stooped, clothes stained, unkempt, more impatient to get his tea on time than for any win. Opening tinned spaghetti, bundling it into the microwave, slamming the door shut “Fiddle-arsing about”, he’d call it.

Then a roar from the lads round the phones and I was back in the Sussex sunshine.

The was entered for the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack writing competition for 2021. The Co-Editor in his acknowledgement warned me that “Probably because of the coronavirus pandemic, we have received significantly more submissions than ever before.” And added he would be in touch with the winner before the end of January 2021. As I never heard from him again I can assume I’m one of the also-rans. Well, it’s the taking part that counts.

This month my father would have been 94.