The Magpie brings us tidings

The Magpie brings us tidings

Of news both fair and foul . . .

And she knows when we’ll go to our graves,

And how we shall be born.

‘How did you choose your parents, Ste?’ He often called me that, Ste. He often just drawled out the vowel and left the ve unsounded. ‘Ha!’ He added a little harrumph for outfoxing me. But he rushed on. ‘I know how I chose mine; I made a mistake, I thought they were bohemians but they were Catholics.’ This time we both laughed, raised beakers of the same pink resiny stuff, made lurid in the poor fluorescent light of the basement.

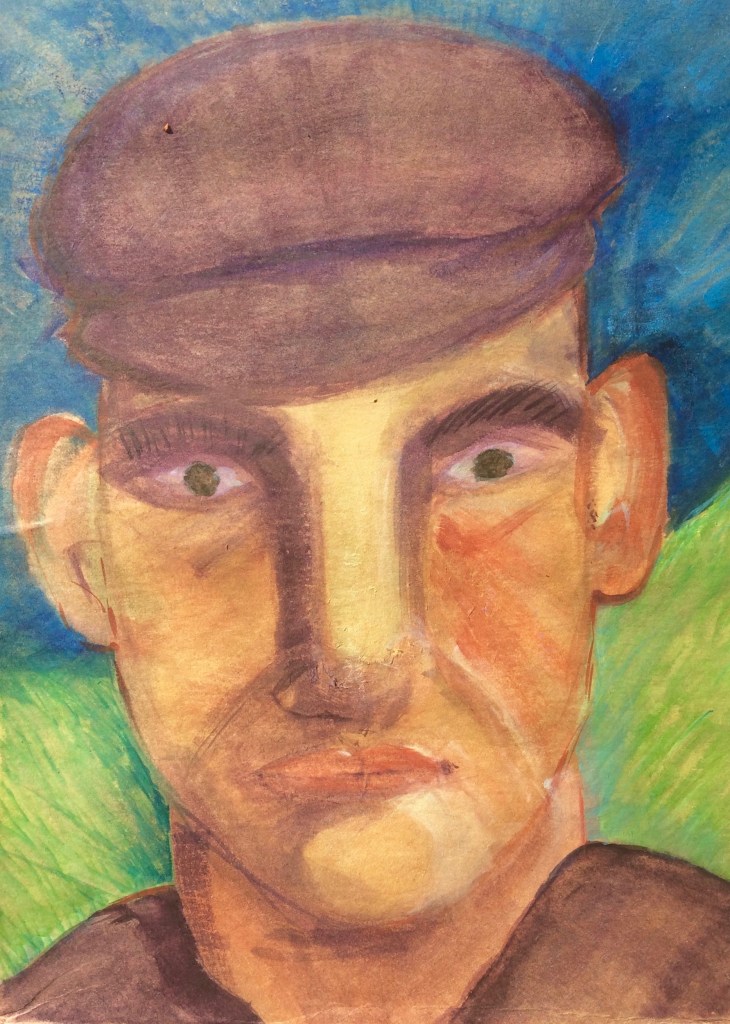

‘You know Finn’ — he resisted the pun, for once — Finn the yoga teacher, he’s thin — ‘One of his Tibetan teachers told him that they know how to choose their parents. A lot of good it did them, some of them.’ Costello’s face was close to mine, opposite: square, handsome, just greying around the temples, lively eyes and a narrow mouth that seemed barely able to keep up with his intelligence.

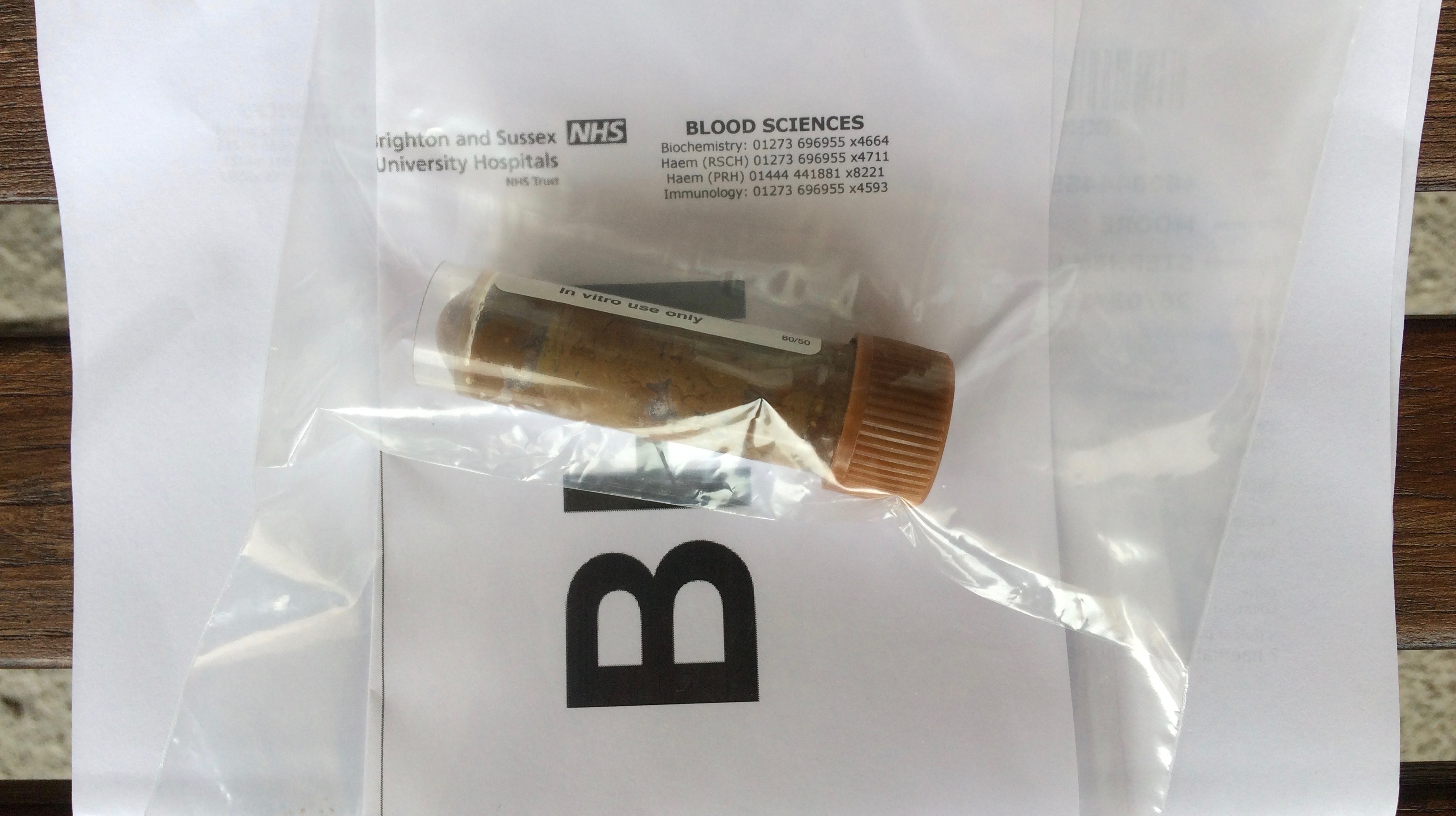

We were in the place where we’d tried to steal one of the tables from outside. ‘They’ve got enough of them,’ he’d said as we made our way down the marble steps into the cigarette smoke and the thick, dense smell of warm olive oil. And the Greeks, in knots of twos and threes, dun-coloured like old woodcock, raising the familiar cacophony that had once sounded like quarrelling. Neither of us remarked that here there were only men. One of them looked on unblinkingly as Costello tugged up a bit of his shirt, pinched an inch of flesh away from his lean belly and injected.

‘Twice a day, Ste, twice a day.’ It was a kind of invocation.

***

I’d wanted to go alone, he knew that, but he’d had followed me out of the spiti, the flat we shared with the others on the edge of town. Lena was cooking that night; ‘She’ll only make a meal of it,’ he’d said. Mostly he talked about the day — the bloody oranges, Andreos our overseer, ‘How much d’you think he makes out of us?’ — but I sensed he really wanted to know where I headed when I wandered off by myself. We went my usual way via the poste restante. There was a letter for me, from my mother. First time, it was always my father who wrote on behalf of the family. Nothing from Isabel.

Costello didn’t bother to check: ‘I wouldn’t want them to write to me,’ he said, ‘Unless there was money, a lot of it.’ He couldn’t raise the will to make it sound shocking. In the restaurant, the letter sat there, unopened; I knew what it must say, that my grandmother, my mother’s mother, had died.

He gossiped on about the Dutch girl; he hardly ever talked about her by name. He was proud that he spent much of our working day chatting to her while me and Hari, her boyfriend, were picking the oranges. ‘You and Hari, up the trees like monkeys!’ There was relish and irony in his sardonic voice, which could never quite cancel out his feeling of wonder at the absurdity of it all. He told me again what we all knew, that her parents were Sannyasins. They meditate in a group in her house. Open marriage.

‘I asked her if they always wear orange, she said it’s more like pink or purple. So, Ste, how did she get parents like that?’

***

‘Lena and Frank say they’re going home for Christmas, they want to be back in time to sign on. There’s a life! They’re like an old married couple anyway, off in their own little room.’ Then he added, ‘What about you?’ I was staying. I was glad, though I didn’t say so, that I didn’t have the money for the Magic Bus back. I ordered more retsina.

There was a surge of half-hearted jeering. We looked up at the tv screen suspended in a low corner, near a grimy pavement light; it showed England, seaside towns I seemed to know, battered by gale-blown seas, lashing rain and great snowdrifts. Even the cars were disabled. The Greek men looked agreeably at one another: hardened by life in Laconia they mocked any discomfort for far away, so-called great, Anglia.

‘Ha! I bet they’ll blame Maggie!’

As we were leaving a waiter came after me, imploring ‘Phile! Phile!’ Stupidly I’d left the letter behind. We’d taken another half carafe and Costello had talked on: about trying to outwit his diabetes and all the authorities back in England who connived in its attempt to quell him.

***

I have the letter in my hand now. I found it while going through my mother’s things after she died; she must have taken it from the small horde of stuff I kept in the box room I used when I stayed. There was no sign of the letter that had eventually come from Isabel (‘I love Huw but I want you too’). I doubt it would have passed my mother’s censor and she would have felt free to destroy it.

My mother’s letter, in a hand like that of a 16 year-old girl, lays out, unaffectedly, the death of her mother in a run down dock town on the Clyde. She recycles the words of the pastor who said ‘She was a good woman.’ I feel struck: there’s no doubt I chose these people, but how and why?

There is a rap at the door, ‘Are you alright in there?’ There’s pleading in my father’s voice, ‘Are you looking for something?’

***

Costello stumbled briefly on the steps as we left. ‘Damn! I’ve forgotten my torch.’ His nighttime blindness always startled me. On the pavement that night I couldn’t tell if he could see me at all. ‘You should see my piss in the morning, Ste; it’ll be solid.’

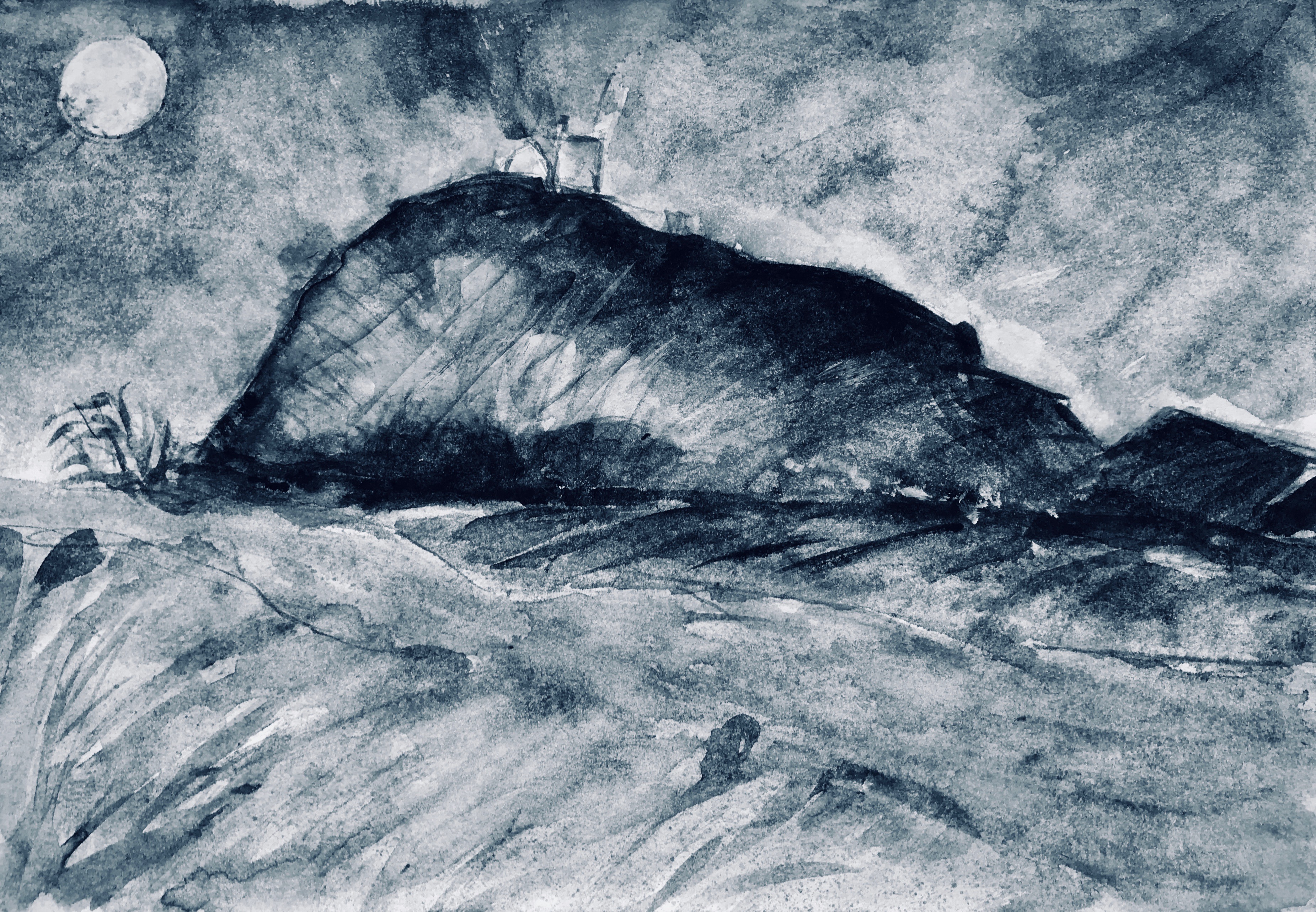

We stood alone on the broad pavement of the empty dark street; a few spindly street lamps doing their best to form shadows. Shut up shops stooped beneath the dull glare of the utilitarian flats above. No moon; a chilly December in Sparta.

I took one of his arms, tentatively, as though under instruction and manoeuvred us into the direction of the spiti, home, then, closer, linking my arm through his. And, for a while at last, I felt the cool, stern compassion of five-fingered Mount Taygetus.

© Submitted to the Creative Future Writers’ Award 2019 run by New Writing South on the theme ‘Home’: it got nowhere. Ah well.

The Magpie brings us tidings

The Magpie brings us tidings